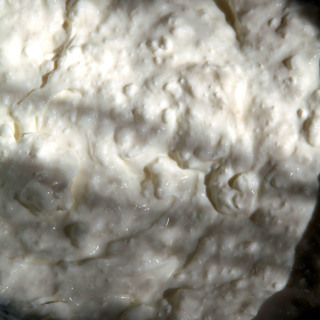

Today at a time of nostalgic return to the simple foods of mum and grandma, a time when it is easier to buy aceto balsamico than vinegar, being modern means buying and eating domestic. The retro wave, because of which at prime time you get roux soup being made on a local TV station, has changed the list of desired nibblers. What in the eighties English tea or smuggled brie and saffron first from Trieste and then from Graz were handmade tagliatelle, cheese and cream, smoked belly bacon and pork renderings from the nearby family farm shop are now. Among the good things that have got a name that today reflect the desires and fears of eaters is basa – fresh, soft, original cheese from Lika.

Simple basa is the expression of the region in which it is made, of the complex relations between people and nature. The story of basa, which according to the informants takes place between us and them, starts with the buša, that modest and hardy shorthorn that for centuries was the only bovine tough and resistant enough to survive in the inhospitable nature of Lika and other hill and mountain regions. The rich (6% fat) milk of the undemanding and adaptable buša lies at the core of rural food; yet this did not save it from being on the verge of extinction. And if we were capable of working strategically and make use of the gastronomisation of culture as the basis of sustainable development, the success and survival story of the boškarin (Istrian long-horned Podolian type of cattle) could be repeated with the buša. Why shouldn’t, let’s say, the existing dairy and cheesery in Otočac not specialise in the making of indigenous cheeses from Lika (škripavac – squeaky cheese, and basa)? Such a cheesery would bring together the existing breeders who would guarantee the home-produced raw material for basa and škripavac. Then one could consider protecting geographical origin and authenticity, which the combination of the plant communities of the Lika meadows and the Lika landraces would absolutely enable. The chain from field to (tourist) table could thus be closed and support itself.