It is Sunday, one before the last one in July and it is quite crowded in Roses, Spain, a summer resort in north Costa Brava. The sun is scorching and the season is reaching its peak, so the little streets along the big marina for yachts and the little fishermen’s harbor, filled with restaurants and shops, are crammed with tourists. The situation is the same on the main local beach and those next to the big hotel monuments to mass tourism lined up a little farther down the shore. And while millions of euros pour into the Spanish tourist treasury, almost none of the tourists (or even the hosts) suspects that the most important era in the history of modern gastronomy is just ending nearby.

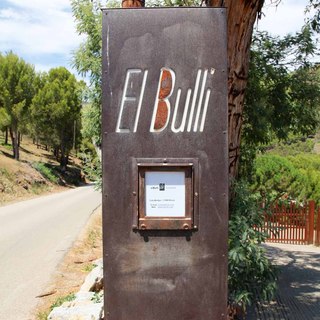

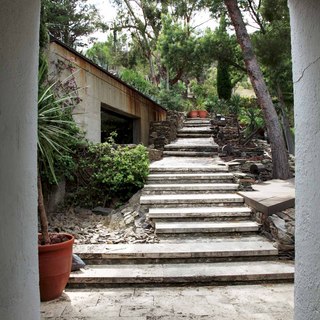

As it happens, only seven kilometers from Roses, some twenty minutes of careful driving on a narrow road winding high above the sea, where bathers enjoying beaches reached via goat paths park their cars on numerous curves, is the remote Cala Montjoi, a bay with a spacious beach – on one end of it is El Bulli (for convenience, we will avoid writing elBulli, which has been the official name of the restaurant for the last ten years), the most important restaurant of our era whose chef, the famous Ferran Adrià, almost singlehandedly turned the way modern generations perceive food upside down, regardless of whether they are supporters of his cuisine, completely neutral gourmets or fierce opponents of molecular gastronomy, as we prefer to call this type of cookery (Adrià and his followers are appalled by this commercialized name and speak merely of science-stimulated creative cooking).

The said end of an era is actually associated with the closing of El Bulli, at least as a classical restaurant. That Sunday, when we set off for El Bulli, Ferran Adrià had only a week left to work, seven dinners to host a total of 350 lucky ones who had the historical honor to witness the last week of operation of this legendary restaurant. The last one of them, on Saturday July 30, was reserved for fifty Ferran’s closest friends and associates and a exactly fifty courses were served (due to the limited number of seats, the arrangements were kept secret, so we surprised Adrià with a question about this dinner of which we had learned from confidential sources).

After intensively arranging the visit since spring (by using all friends and people we know in the culinary world), a positive reply had arrived no sooner than three weeks before. As global media had fiercely swarmed on El Bulli during its last season of operation (interviewing Ferran Adrià during the last days of operation of the most important restaurant in the history of gastronomy was a huge challenge for gastro writers), the achievement exceeded by far even the confirmed table reservation, an event that equals winning the lottery in case of this restaurant. As it happens, El Bulli claim they receive two million reservation requests a year for around eight thousand seats during the season (a number hard to believe, for technical reasons if nothing else), a chaos that is primarily a result of five first places won on the famous list of world’s fifty best restaurants (2002, 2006, 2007, 2008 and 2009) published every year by the British Restaurant Magazine. It is because of this list that El Bulli has often been spoken of during the past decade, even by general practice gourmets across the world.

However, if we look back, in the second half of the 1970s it seemed Fernando Adrià Acosta, born 1962 in the Santa Eulàlia quarter in Hospitalet de Llobregatu (a town southeast of Barcelona that is often incorrectly referred to as its suburb) would become a good footballer rather than a world-famous chef. Still, in 1980 he became a cook apprentice and did not like the job very much. However, while serving in the navy (as a cook), destiny interfered with his life for the first time. During a short leave, his colleague Fermi Puiga (presently a popular Catalan chef) who had already worked at El Bulli, talked into visiting this restaurant near Roses in 1983, which then proudly wore two Michelin stars, and he decided on the spot to come work there after he finished his military service.

Four years later, destiny intervened again, so Ferran became head chef at El Bulli and at the same met the French chef Jacques Maximin in Nice, who told him – Creating means not copying, a term that determined his professional path (At the time, the term creativity was reserved for artists only, and not for chefs. Maximin helped me realize that I too am entitled to create, says Adrià).

As early as 1990, he managed to restore the second star for El Bulli, which had been lost in the meantime by his predecessor (the third one was awarded in 1996). That same year, Adrià managed to purchase the restaurant from its founders together with the head waiter Julio Solero (who had worked at El Bulli before Ferran joined them and still co-owns it with him), whereby destiny continued its game of unusual coincidences. That is when the creative phase of El Bulli has begun, initiated by Ferran’s table of associations (possible combinations of ingredients, culinary technique, emulsions, herbs, condiments …) and continued with a phase called Elaborationes (development of concepts techniques), only to culminate between 1994 and 1997. The foundation for all this was the Catalan cuisine in combination with local ingredients and additives adopted from the confectionery industry. By using this range, Adrià began to change the textures of ingredients, seek out their new combinations, deconstruct traditional and classical dishes and create avant-garde dishes of amazing properties that played with the palate, sense and guest views, shrewdly hinting at tradition and cultural aspects of food, but also often boldly provoking (for example, Adrià used raw rabbit brain in many of his creations). Thanks to all this, he developed a peculiar culinary vocabulary that delighted may people, but also created many enemies (criticism was mostly directed at the unnaturalness of food and their harmfulness for health although the additives he used were mostly of natural origin).

The creative process was very much supported by the fact that, due to a lack of guests, El Bulli was closed in winter (a habit that Adrià inherited from the previous owners when there were no guests in the off-season), so this time was dedicated to experimenting, developing new concepts, techniques and dished (at first at the testing ground restaurant Talaia Mar and then at the culinary studio-workshop Taller, both in Barcelona). Ferran selflessly shares his creations and achievements with everyone, so an army of his (mostly bad) imitators emerged at the turn of the millennia and even the least gifted cooks began to incorporate his aromatized foams in their dishes. Ferran’s unusual and radical style also attracted the media, who came up with the awkward term molecular gastronomy and definitely created the myth of El Bulli together with Restaurant Magazine’s Pellegrino World’s 50 Best Restaurants list.

When he announced he was closing the restaurant for two years in January last year at the Madrid Fusión Adrià gastro event, the news rapidly spread around the globe and even found its way to the front pages of some of the leading dailies. Less than three weeks later, while world’s foodies though of new ways to get a reservation during the next two seasons, Adrià announced he was actually closing down permanently. The gourmet madness then went to extraordinary lengths. The reasons for the closing were probably in the fact that the restaurant was incurring excessive losses, but also in Ferran’s realization that his basic mission was over and that some younger colleagues beat him in his own game in the meantime and advanced his philosophy, and that El Bulli has gradually, it’s odd to even say it, become obsolete. In autumn of 2010, Ferran’s team announced the establishment of the El Bulli Foundation that would hold workshops in the restaurant, involving chefs from across the globe (former Taller’s role), where the restaurant, reduced in volume, would be just an amenity.

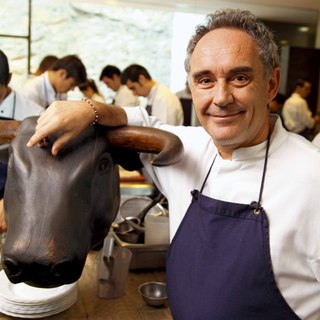

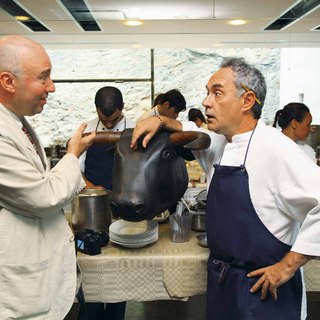

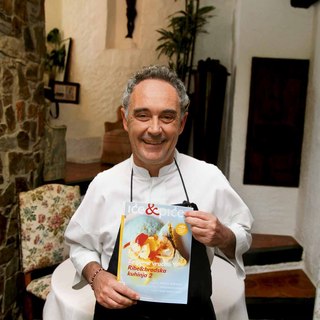

On that Sunday afternoon, Ferran Adrià himself met us at the entrance to El Bulli standing by a desk with his associates and arranging the last details regarding the menu for that evening. This 49-year-old of medium built, with curly black hair with grey around the edges, a penetrating gaze and sustained bearing, surprised us with his willingness to pose for photographs, but also with the mistrusting way he started the interview. However, after some ten minutes he quite unexpectedly said: I see you’ve studied our work well and few do it thoroughly. I’ve gave a thousand interviews, but only a few journalists followed our work so carefully. After the interview he became much more casual, though not deprived of his rapid and passionate speech and firm attitudes. After an hour (a duration of interview unprecedented in Adrià’s case), he even agreed to answer some additional, more personal questions. Finally, when we thanked him for his time and good will, he replied: Thank you for spending your time on studying the history of El Bulli. I can’t recall the last time I gave such an interesting interview – we then smiled and thanked him, taking the gesture as courteous. Realizing what we were thinking, Adrià suddenly became solemn and added: No, no. You have no idea how many journalists come here without knowing anything about El Bulli. He then returned to the kitchen where his three equal chefs, six cooks and 32 stagiaries (cooking interns, in case of El Bulli experienced cooks from world’s best restaurants), all wearing blue aprons (before the actual serving, only Adrià and the chefs would put on freshly ironed white blouses), were in the middle of preparing for the evening in complete silence, a scene that looked more like a routine experiment in the laboratory of a space ship than a classic kitchen (no flame was to be seen).

This completely original organization of work in the kitchen is only the tip of the iceberg in Adrià’s overall contribution to gastronomy. Over some twenty years of intensive development, during which he presented a menu of thirty courses every season with new dishes and those that had evolved over time (there were around fifty dishes on the repertoire every year and each of the fifteen tables was assigned a different menu derived from the repertoire), Adrià has defined his style based on three pillars, technical and conceptual research, the role senses in creation and during eating, and the role of reason and its impact on the act of eating. His culinary philosophy arose from all this and is also his greatest contribution to the history of gastronomy. Among other things, it includes serving of small portions and numerous courses, finding new ingredients, working with contrasting textures and temperatures, the assumption that all ingredients can have the same potential (turnip and sardines are as valuable as caviar and truffles), and the idea that each dish must contain an element of surprise. These are the postulates that have been adopted by all chefs in the world that are at least a little ambitious. In addition, Adrià has had immeasurable influence in the form of developing culinary techniques (foams, spherification, use of liquid nitrogen…), mostly to enhance the taste of high-quality ingredients, many of which have already become part of the culinary mainstream (an encyclopedia will soon be published, dedicated only to this segment of Ferran’s work).

Adrià’s influence on young chefs across the world is also very important. If we only mention the many first-league players in contemporary creative cooking that passed through his kitchen as stagiaires – José Andrés, René Redzepi, Andoni Luis Aduriz, Massimo Bottura, Joan Roca, Graham Elliot Bowls, Grant Achatz…, it is clear that the giant leap Ferran Adrià has taken in the history of gastronomy will also be a driver of the culinary future.

Regardless of how the new Foundation Ferran Adrià is preparing with his associates will function and what role El Bulli will play in it, it is quite certain that the world Adrià has created will continue to have a strong impact on the future of gastronomy. Still, whether the famous chef admits it or not, an era in the history of gastronomy is definitely over, with which some of his best friends and colleagues agree. This is why we began this interview with the most influential chef of our era with a question about the gravity of the moment.

Mr. Adrià, how do you feel immediately before the beginning of the last week of service at El Bulli?

Look, El Bulli has been closing for six months every year for decades now, so the present feelings are not very difference. We are not thinking about the significance of the end of this season. July 30 will be a special day because we will have a big celebration. This is the only reason.

Are there perhaps any mixed emotions – satisfaction, pride, nostalgia, sadness...?

There are no such emotions. They will probably appear in January or February when we realize that a transformation has taken place. I know everybody is talking about how El Bulli is closing, but we are not actually closing it. This is very important to know. If we were actually closing it forever, of course we would be sad and nostalgic, but we are now very pleased because we will actually celebrate the beginning of a new project. We are not celebrating the past, but the future.

How well do you remember your first day at El Bulli in the summer of 1983?

The clearest memory is of the moment they came for me. I was in Roses and we departed for El Bulli. A very bad road leading to the restaurant remained carved in my memory. It looked nothing like today. I thought it was some kind of a joke because the road was not even asphalted yet. It looked like it led nowhere, least of all a restaurant. When I arrived, I was most impressed with the cooks’ attitude toward their work. I immediately noticed that cooking was more than just work for them. They enjoyed what they were doing.

El Bulli already had two Michelin stars at the time. What was your impression with the kitchen and the dishes?

Yes, the restaurant prepared French dishes at the time based on the principle of nouvelle cuisine and this was quite mimetic, a copy of some French role models. You could see a creative spirit was already present, but clearly to a much lesser extent than today.

You were quite familiar with the principles of nouvelle cuisine at the time. How much help did you get from the famous series of the Parisian publisher Robert Laffont, presenting the leading chefs of the movement?

Very much. I had La cuisine c’est beaucoup plus que des recettes by Alain Chapel, La cuisine du marché by Paul Bocuse, La grande cuisine minceur by Michela Guérarda, the Troigros brothers book... At the time, high cuisine was exclusively French and there was no need to look any further.

How would you describe yourself in 1987 when you became head chef at El Bulli and met Jacques Maximin?

I was very young, 25 or 26, and was beginning to think of my work more seriously, although still at some subconscious level. I began to look for my way and form my own ideas. Little by little, I began with attempts to transfer the nouvelle cuisine principle to the Spanish cuisine. Actually, at first to the Catalan cuisine, and then to the rest of Spain.

When was the first time you seriously began to think about how the usual textures of some ingredient could be altered?

This happened much later. First we began to work on modernizing the Spanish cuisine and there was no talk of alternating the textures. That came much later. We didn’t begin with this before 1991 and 1992. This is where you see what’s most important for El Bulli – constant development. We develop year after year.

The idea of alternating the texture of ingredients resulted in a big leap in development of modern gastronomy. How did you come up with it?

To be honest, textures have always been changed. I wasn’t the one to invent it. For example, when you prepare strawberry soup, the texture changes completely. What I do is create new textures and this is something completely different. However, it is a general misapprehension that we changes textures in all dishes. This is not the case at all, there are plenty of dishes where we don’t affect the texture of the ingredients at all.

Do you believe the table of associations from 1990 the foundation of the style you developed in the 1990s?

Combining ingredients and flavors is an integral part of any cook’s work. This is something quite normal and all cooks do it. My intention was to codify all this and classify it in an organized manner. It turned out this creative system worked excellently here. We could say this was a foundation for us and sort of the easiest way of creating.

You have already mentioned that evolution is very important for what you do. To what extent was El Bulli a revolution over the past twenty years?

It was not a revolution at all. We never speak of revolution because we never speak of the past negatively, on the contrary, only very positively.

Has revolution always been something negative to you?

No, not necessarily, although it often destroys everything that preceded it, whether good or bad. In this context, our work was no revolution. It is a different matter that the result of our revolution was revolutionary. Not because I aspired toward this. This is a very interesting fact. Nouvelle cuisine was much crueler to its predecessors.

Were you aware during this evolution that you were building something of great importance for the future of gastronomy?

When we began to do these things, we were not aware of it. Time ultimately always tells, so we can now confirm they were important steps, But in the 1990s, we could not say that. Somebody could have thought it was just fashion. Some could have thought we were unauthentic. But now I can say this is a movement with great influence across the world.

What made you begin to think about concepts and techniques in 1993, rather than creating new dishes, about what you refer to as Elaborationes?

It’s very simple. It was usual to create dishes and that’s normal. But we said no, we want to create techniques and concepts that will make room for creation of many new dishes. This is a complete change of paradigm in cooking and most likely the most important fact concerning El Bulli.

How did you develop your culinary philosophy, implying serving of small portions, looking for new ingredients, working with textures, deconstruction, the awareness that even the most common ingredient has huge potential, as well as the element of surprise essential to each dish?

The most important thing to underline is that the new expression was created between 1994 and 1997, followed by development of this expression. Food is a language, a way of communication and understanding. It is as if you are telling somebody something with it, expressing yourself. Like every nation has its cuisines as part of its culture, the same applies to our expression. By using my creativity, I contribute to the expression of the team I am working with.

Did the winter breaks at El Bulli and then Talaia Mar and then Taller provide you with monastic conditions for creative development and how crucial was this for the evolution of your cooking?

It is not about monastic working conditions, but the fact that creation takes time. This is very simple and there is no secret about it. Simply, to be able to create, you need time. Of course, this was not the first time somebody has thought this way. Why? Because later it gets more and more difficult to create every time. Namely, something new is created day after day, so there is less and less room for creativity. It takes more time, more people, more equipment... The El Bulli Foundation is a logical consequence of such thinking.

In addition to time, did you require peace for creative work?

Look, in the beginning we closed for six months because nobody came here in winter. There were no guests. We are at the seaside in winter as well and there is simply no one here. Later this circumstance became an opportunity for creation. But I do not require any extra peace. There is always a time for peace and a time for activity.

What was the technology of creating new dishes based on concepts and techniques like?

Now we come across one of the big lies about El Bulli. There was never any technology in creation at El Bulli. A microwave oven is much more complicate than a siphon. Unfortunately, many people concluded it was technology based on a few photographs. If only we had technology to do great things! However, there is presently very little of such technology. We created a new concept, but probably didn’t explain it well enough.

Do you like to do schemes of new dishes, draw on paper...?

Not really. We don’t draw everything, but we mostly record everything, in writing and photographically. Depending on the year and the circumstances.

Is it always teamwork?

Yes, but in the beginning it was mostly my brother Albert and I.

The year 1997 is mostly referred to as the year provocation in your career. Did you knowingly step onto unknown territory?

I would rather says that we looked at cooking differently until 1994 and that our perception of cooking was within the boundaries of something we described as very good and very tasty. However, since 1994 we began to aspire to certain experiences including some new elements, such provocation and wit, different approaches that had not been used before in creation of dishes. We began to consider food in a different way. This is one of the most important qualities of El Bulli. This had not existed before. Or rather, it had not been conceptualized before. It is not important who did something first, but who conceptualized it. For example, who invented the mini skirt? Mary Quant? No, the ancient Romans wore very short skirts. So what did Mary Quant do? She conceptualized the mini skirt.

How did you try to provoke?

There are many ways to provoke. It depends on the person you want to provoke. At first we did it one way and then in many other ways. For example, you can provoke with poetry because many people who visit El Bulli do not expect poetic food. They expect dishes with a higher dose of technology, for example. It depends.

For example, your dish made of sea anemone, raw rabbit brain, oysters and calamodina (a type of South Asian citrus, authors comment) is described by some as repugnant, while your biographer Coleman Andrews, who has eaten many times at El Bulli, finds it very unpleasant and cacophonic?

No, no, no. He was the only one who didn’t like the dish. (Not quite true because Coleman described how one of the interns in the kitchen that the great San Sebastian chef Juan Mari Arzak, one of Adrià’s best friends and a frequent guest at El Bulli, furiously stormed into the kitchen after trying this dish one evening and asked Ferran if he was insane, author’s comment)

Was this perhaps a provocation?

Oh, no. Provocation for whom? There were other people who were not provoked by this dish at all. It also depends on the culture. For example, rabbit brain is very provocative to an American and not for a Spaniard. And there is also the problem with children because many keep a rabbit as a pet, like a dog. How would you react to dog brain? In Hong Kong, this is quite a normal dish, but to an America, however open to new ideas, this is completely insane. There is no strange food, only strange people. Food is always food.

Why do you use raw rabbit brain and ears so often, even within a single menu?

Why not?

Is it provocation?

No, it’s not provocation. We work with these ingredients because they are not used so often. A man can eat a suckling pig’s ear with no problem, but is appalled when offered a rabbit ear.

Suckling pig is also a taboo for many people and a completely normal dish in many cultures around the world?

Yes, yes. For example, I don’t eat rats.

Why not?

Rats are a taboo to me and I think I would be sick. In Amazonia, I tasted the meat of a smaller rodent and that was my limit. I wouldn’t try a rat or any rodent of that size.

In some parts of Dalmatia, especially on the island of Brač, dormouse, also a smaller rodent, is considered a delicacy. Does that sound strange?

No, it doesn’t. But I don’t know if I would eat it, I’d have to see it first, I don’t know. Actually, when speaking of creativity, discussions like this make no sense. Cultural facts must not manipulate creativity. Of course there may be some things that are a taboo to someone. I wouldn’t eat a rat, but I might try a giraffe.

They say breast milk has umami taste, but it is a taboo?

Yes, it is a taboo too. But every taboo is a cultural issue, not a real one.

Many of your dishes refer to the Catalan folk tradition, like the goatfish mummy with chili (fried goatfish bone in aromatized cotton, author’s comment), that actually reminds us of the fact that poor fishermen used to sell fillets and eat fried fish bones and heads. Do you like to toy with the cultural context of dishes?

Yes, yes, certainly. It’s just that culture is not a simple term. It depends on what we’re talking about, the geographic, political or another segment of culture. This was a matter of geography and tradition. Some understood it and some did not...

Back in 1998, you had the idea of expanding the Benazuza (a luxury hotel chain project, authors comment) concept to other Mediterranean locations, including Mallorca and Croatia. Did you give it up because the hotel business seemed too risky?

Yes, yes. Fortunately, we did not make the El Bulli Hotel. I thus prevented all that could have happened in this crisis. It is very difficult to make and maintain a luxury hotel in Europe. Why? Because the labor is very expensive and it is impossible to survive that way. This is why most luxury hotels are not here, but in far countries.

Was this project also interesting as a means of spreading your culinary philosophy?

It’s not just that. I am interested in hotels as such, not just the food in them. I like the spirit of a hotel. It is therefore not merely about the culinary philosophy, but the life philosophy. For example, we have many boring hotels today, but I think it’s OK to have more amusing areas as well. Going for lunch or dinner to a hotel currently seems like going to a monastery. I think it should all be a bit more relaxed.

Is it true that you are reopening Hotel Benazuza in Seville in March of 2012 and why?

Yes. That’s true. Because the owner wants to do so. We are friends and I want to help him. But it’s very difficult to operate a hotel located outside the city today in Europe, especially when it comes to luxury hotels. Such business concept is really very difficult. There are plenty of problems in smaller hotels, especially with respect to the proportion between the number of employees and the number of rooms.

Many young chefs follow your work. What would you recommend them, how to think?

First of all, a young chef must always look up to different role models and then decide which role model makes him happiest. Secondly, he must inquire with people having more experience about what job would be the best for him. Because, when a man is young, he thinks everything is easy and that is not so. For example, it is ten time more difficult to run a restaurant outside the city than a city restaurant. This is something you simply must know. Also, one should keep in mind that there are not so many people having business lunches anymore. Therefore, I would recommend young chefs who want to start a business to ask their elders for advice.

As for cooking, what proportion between tradition and modernism would you recommend?

They can do whatever they want in the kitchen. Let then prepare food that will make them happy. Don’t think I am saying this lightly. This really is the essence.

Over the past twenty years, you have been considered to be the most influential chef in the world? What doe being the best chef in the world mean to you personally?

Four years ago I never thought about it. There were people who thought we had a negative influence on young chefs. But as our positive influence is an actual fact today and something measurable, it is now widely recognized. Most presently leading chefs in the world have visited El Bulli. And this is really nice. Nice for all of us who are part of El Bulli. And El Bulli is not just Ferran Adrià, it is a spirit for itself. And we all form it – two thousand people who have worked here and around a hundred thousand people who have eaten here. It’s a good thing this idea will continue through the El Bulli Foundation.

Did Restaurant Magazine’s San Pellegrino list help the influence of this spirit?

This list is good insomuch as Michelin no longer has a monopoly. I would like it if there were a few more such awards, brands competing against each other. Just like in the film industry, where we have the Oscar, Cannes, Berlinale... It would be good if the number rose from two to five such authorities.

What do you think about Michelin?

Michelin is a very serious brand. However, it will have to adapt to the future just like the rest of us. And future is the internet, especially for restaurant guides. You need to be very active. Classifying something for the next year no longer makes sense. We know that there are many blogs today where people, unlike guides, comment on restaurants and food in detail. The Financial Times published an article dealing with this exactly. The conclusion is that you need to reorganize yourself. Like you and me and all of us. However, Michelin is still a serious guide. Unfair, though, like any other.

Your cuisine has many followers, but many critics as well. How do you most often respond to criticism that your dishes are not natural?

Thank God, I will no longer have to respond. A new era has begun and I no longer want to waste time on such questions. I think we’ve shown the world all that needed to be shown. It is simply impossible to continue to claim that the most influential restaurant in the world is poisoning people. The schizophrenia no longer makes sense. After all, time will always tell.

Considering the experience wit Documenta 12 in 2007 (Adrià was invited to participate in a prestigious art exhibition in Kassel, Germany, author’s comment), do you think of food as a form of art and can it be a form of art?

There is also a book about this and a documentary has been made. To me, the most important thing is the dialog between cuisine and art, these two creative worlds, or worlds that may be creative and are just starting a dialog. But I think it is not good to ask whether cooking is art. In 2011, it makes no sense because the world has changed. The question makes no sense.

Your new foundation with associates from all over the world will probably set new challenges to the cuisine of the future for years to come. What does its slogan Freedom of Creation mean to you?

Freedom of Creation is a changed old motto – Creating Is not Copying. Therefore, in 1986 the motto was Creating Is not Copying, and in 2014 it will be Freedom of Creation. Both are metaphors. What does this mean? This means freedom is the dream of each creative person. The more freedom, the better.

You already mentioned that almost all the most important young chefs today have worked in El Bulli’s kitchen. In your opinion, what is the most important thing you conveyed to them?

First of all, the passion for what they do. Secondly, sharing your experience with other people. Thirdly, taking risk. This is the spirit of El Bulli.

As its success grew, El Bulli became more and more inaccessible and the expansion of creativity impeded the normal operation of the restaurant. Could we say that closing the restaurant is actually the last phase of its evolution?

This is natural growth. I see you have studied the history of El Bulli. You are right, after Taller, El Bulli’s workshop, the Foundation is the natural sequence of events. The El Bulli Foundation is a fusion between the El Bulli restaurant and the El Bulli workshop, like a cocktail. This is strange, but it was also strange when we launched the workshop, because there was nothing similar anywhere in the world at the time. The idea behind the Foundation is actually the spirit of El Bulli – we feel a passion for this job, we share experience and take risk. We will see what will happen. Still, I would say this is primarily a scenario for the future life of El Bulli. All other restaurants, especially at this level, must change after some time because they simply go under or begin to deteriorate, which is even worse. I think this project will keep the spirit of El Bulli alive for many years to come.

What will happen with Taller?

It will be a nice place for drinking gin & tonic. I’m joking. We will move the workshop here. We thought about selling it, but we later realized it was a historical place, the first gastro workshop in the world. We will use it to receive visitors, there will be tours like in a museum, and it will also serve as a conference area.

Taller is a very modernly designed space. Why did you let the premises of El Bulli, which have not been significantly changed since the 1960s, to remain in such disproportion with the dishes served in it?

When we first thought about redesigning the interior, we didn’t do it for lack of money. Later, when it became financially possible, I realized it wouldn’t be good. We serve very special, avant-garde food and it seemed necessary to leave the guests at least some contact with the real world, so we didn’t redesign the interior. I will give you a radical example. When you are given a medication in a hospital, you will have a different reaction than if you were given the medication here on the beach, for example. You understand? This is what’s happening here. All this strange food in a normal place like this.

And this is a sort of an element of surprise?

Yes, that’s correct. Above all, it is important to keep the provocation within certain boundaries and not cross it because people will otherwise not be able to enjoy the provocation.

Is there anything you regret in your career to date and the era in El Bulli?

You shouldn’t think about things you can’t change. There is no point if there is nothing you can do. Why talk about it? One should learn lessons from the past and that’s all.

You do not think about the past at all?

Yes, I do. It’s just that I do not think about whether I have done something good or bad, but simply about what happened.

What do you plan to do when you close the restaurant next week?

As always – travel. To China, Peru, United States, Argentina...

Business or pleasure?

Both, of course. One should combine them. I do it like that every year. But I will not see the difference before January, when we would normally open the restaurant. Instead, we will begin to work on the Foundation. But the situation is now very similar to what we do every year.

Is it true that you live a very simple life and are not a materialist?

Yes. I live a simple life, I have a small car... I don’t need much. But I love to travel. I love hotels and I love food. When someone invites me to their boat, I gladly accept, but I have no intention of buying my own yacht. I can rent one, which I do occasionally.

Did you inherit your modesty from your parents?

Yes and no. I lived very modestly with my parents for fifteen years and became used to it. This is normal to me.

You once said you were very cold and calculated professionally and very warm privately. How is it possible to reconcile these two completely different sides of your personality?

Private life is one thing and business is another. There are seventy of us working here and we must separate one from the other.

Do you have a big ego?

Even if I do, I have justified it a hundred times over (smile).

You say the act of eating is very complex. How is this possible in case of daily routine?

What do you mean? We can look at a painting every day and it still may be a complex thing. When I say complex, I refer to the fact that this may be the only discipline where we use all five senses.

Is it also important that we train these five senses every day?

No, this doesn’t matter at all. I practiced football every day and still never became a professional footballer. For those in cooking, or gastronomy, it is very important to understand that the fact that someone eats every days does not mean they know how to eat. You need to have a certain gift for it. For example, you can play golf every day and still be a very bad player. On the other hand, there are people who play very rarely and are excellent. It took me a long time to discover this. You can see may gourmets in restaurants that we normally refer to as foodies, amateurs who visit restaurant a lot. I’ve heard them talking, seen them eat and realized they understand absolutely nothing. Not in El Bulli, though. When I see them, I think to myself how weird they are! This is why I gave you the example of football because the fact that you practice every day means nothing in itself.

As long as you are mentioning football, we know you played the sport as a young man and dreamed of having a career as a professional player. Do you think that, if you applied the same philosophy you used in creating your cuisines, you would have become an equally good footballer as you are a chef?

No. This does not work on the principle of communicating vessels. There are no universal rules in life.

You do not regret not becoming a professional footballer?

No, I don’t regret it.

Do you believe in destiny?

No, I don’t believe in destiny because otherwise there would not be so many people starving to death. I don’t believe their destiny is to starve to death.

How did you feel last year when Noma, the restaurant owned by you student René Redzepi, replaced El Bulli El Bulli in the top position of the San Pellegrino list?

Fantastic. But it’s not merely about being number one, but also about being number two, three, four, five and six. Redzepi, Joan Roca, Massimo Bottura, Grant Achatz... they all worked here. This is fantastic.

Are you proud of this?

Not me, El Bulli is.

On Saturday, in six days, you will be host to your friends, associates and some of the chefs you have mentored at the last dinner in El Bulli. What will that evening be like?

This will not be a party, but an homage to the people who created El Bulli. Some of them come as representatives of the two thousand people who have worked here.

Will there be any surprises?

I am an expert in surprises.

What will you serve that evening?

Nothing special, ordinary people are coming so we won’t prepare any special dish. El Bulli will simply pay respect to the people who created it. It will be very simple. (Not quite true, because fifty guests were served all fifty dishes from this season’s repertoire and, according to some people who were there, the party went on until the early morning hours, author’s comment)

Will there be a little nostalgia as well?

What? You mean the last day? No way. I couldn’t be happier. The entire gastro world is envious of us. I now finally have two and a half years to study, travel, to make a new beginning... How could I be sad about this?

Finally, where do you see yourself in ten years?

Here. At the Foundation. This is exactly the difference. I could stay at the El Bulli restaurant for 3-4 more years, no more. I will remain at the El Bulli Foundation for the rest of my life. This will be a completely different job.